Description: How to Read a Book by Mortimer J. Adler, Charles Van Doren Synopsis coming soon....... FORMAT Paperback LANGUAGE English CONDITION Brand New Publisher Description How to Read a Book, originally published in 1940, has become a rare phenomenon, a living classic. It is the best and most successful guide to reading comprehension for the general reader. And now it has been completely rewritten and updated. You are told about the various levels of reading and how to achieve them -- from elementary reading, through systematic skimming and inspectional reading, to speed reading, you learn how to pigeonhole a book, X-ray it, extract the authors message, criticize. You are taught the different reading techniques for reading practical books, imaginative literature, plays, poetry, history, science and mathematics, philosophy and social science. Finally, the authors offer a recommended reading list and supply reading tests whereby you can measure your own progress in reading skills, comprehension and speed. Back Cover How to Read a Book How to Read a Book, originally published in 1940, has become a rare phenomenon, a living classic. It is the best and most successful guide to reading comprehension for the general reader. And now it has been completely rewritten and updated. You are told about the various levels of reading and how to achieve them-from elementary reading, through systematic skimming and inspectional reading, to speed reading. You learn how to pigeonhole a book, X-ray it, extract the authors message, criticize. You are taught the different reading techniques for reading practical books, imaginative literature, plays, poetry, history, science and mathematics, philosophy and social science. Finally, the authors offer a recommended reading list and supply reading tests whereby you can measure your own progress in reading skills, comprehension and speed. Author Biography Dr. Mortimer J. Adler was Chairman of the Board of the Encyclopedia Britannica, Director of the Institute for Philosophical Research, Honorary Trustee of the Aspen Institute, and authored more than fifty books. He died in 2001.Dr. Charles Van Doren earned advanced degrees in both literature and mathematics from Columbia University, where he later taught English and was the Assistant Director of the Institute for Philosophical Research. He also worked for Encyclopedia Britannica in Chicago. Table of Contents CONTENTSPrefacePART ONETHE DIMENSIONS OF READING1. The Activity and Art of ReadingActive ReadingThe Goals of Reading: Reading for Information and Reading for UnderstandingReading as Learning: The Difference Between Learning by Instruction and Learning by DiscoveryPresent and Absent Teachers2. The Levels of Reading3. The First Level of Reading: Elementary ReadingStages of Learning to ReadStages and LevelsHigher Levels of Reading and Higher EducationReading and the Democratic Ideal of Education4. The Second Level of Reading: Inspectional ReadingInspectional Reading I Systematic Skimming or PrereadingInspectional Reading II: Superficial ReadingOn Reading SpeedsFixations and RegressionsThe Problem of ComprehensionSummary of Inspectional Reading5. How to Be a Demanding ReaderThe Essence of Active Reading: The Four Basic Questions a Reader AsksHow to Make a Book Your OwnThe Three Kinds of Note-makingForming the Habit of ReadingFrom Many Rules to One HabitPART TWOTHE THIRD LEVEL OF READING: ANALYTICAL READING6. Pigeonholing a BookThe Importance of Classifying BooksWhat You Can Learn from the Title of a BookPractical vs. Theoretical BooksKinds of Theoretical Books7. X-raying a BookOf Plots and Plans: Stating the Unity of a BookMastering the Multiplicity: The Art of Outlining a BookThe Reciprocal Arts of Reading and WritingDiscovering the Authors IntentionsThe First Stage of Analytical Reading8. Coming to Terms with an AuthorWords vs. TermsFinding the Key WordsTechnical Words and Special VocabulariesFinding the Meanings9. Determining an Authors MessageSentences vs. PropositionsFinding the Key SentencesFinding the PropositionsFinding the ArgumentsFinding the SolutionsThe Second Stage of Analytical Reading10. Criticizing a Book FairlyTeachability as a VirtueThe Role of RhetoricThe Importance of Suspending JudgmentThe Importance of Avoiding ContentiousnessOn the Resolution of Disagreements11. Agreeing or Disagreeing with an AuthorPrejudice and JudgmentJudging the Authors SoundnessJudging the Authors CompletenessThe Third Stage of Analytical Reading12. Aids to ReadingThe Role of Relevant ExperienceOther Books as Extrinsic Aids to ReadingHow to Use Commentaries and AbstractsHow to Use Reference BooksHow to Use a DictionaryHow to Use an EncyclopediaPART THREEAPPROACHES TO DIFFERENT KINDS OF READING MATTER13. How to Read Practical BooksThe Two Kinds of Practical BooksThe Role of PersuasionWhat Does Agreement Entail in the Case of a Practical Book?14. How to Read Imaginative LiteratureHow Not to Read Imaginative LiteratureGeneral Rules for Reading Imaginative Literature15. Suggestions for Reading Stories, Plays, and PoemsHow to Read StoriesA Note About EpicsHow to Read PlaysA Note About TragedyHow to Read Lyric Poetry16. How to Read HistoryThe Elusiveness of Historical FactsTheories of HistoryThe Universal in HistoryQuestions to Ask of a Historical BookHow to Read Biography and AutobiographyHow to Read About Current EventsA Note on Digests17. How to Read Science and MathematicsUnderstanding the Scientific EnterpriseSuggestions for Reading Classical Scientific BooksFacing the Problem of MathematicsHandling the Mathematics in Scientific BooksA Note on Popular Science18. How to Read PhilosophyThe Questions Philosophers AskModern Philosophy and the Great TraditionOn Philosophical MethodOn Philosophical StylesHints for Reading PhilosophyOn Making Up Your Own MindA Note on TheologyHow to Read "Canonical" Books19. How to Read Social ScienceWhat Is Social Science?The Apparent Ease of Reading Social ScienceDifficulties of Reading Social ScienceReading Social Science LiteraturePART FOURTHE ULTIMATE GOALS OF READING20. The Fourth Level of Reading: Syntopical ReadingThe Role of Inspection in Syntopical ReadingThe Five Steps in Syntopical ReadingThe Need for ObjectivityAn Example of an Exercise in Syntopical Reading: The Idea of ProgressThe Syntopicon and How to Use ItOn the Principles That Underlie Syntopical ReadingSummary of Syntopical Reading21. Reading and the Growth of the MindWhat Good Books Can Do for UsThe Pyramid of BooksThe Life and Growth of the MindAppendix A. A Recommended Reading ListAppendix B. Exercises and Tests at the Four Levels of ReadingIndex0 Review "These four hundred pages are packed full of high matters which no one solicitous of the future of American culture can afford to overlook." -- Jacques Barzun"It shows concretely how the serious work of proper reading may be accomplished and how much it may yield in the way of instruction and delight." * The New Yorker *"There is the book; and here is your mind. Adler and Van Dorens suggestions on how to connect the two will make you nostalgic for a slower, more earnest, less trivial time." -- Anne Fadiman Long Description How to Read a Book,originally published in 1940, has become a rare phenomenon, alivingclassic. It is the best and most successful guide to reading comprehension for the general reader. And now it has been completely rewritten and updated.You are told about the various levels of reading and how to achieve them -- from elementary reading, through systematic skimming and inspectional reading, to speed reading, you learn how to pigeonhole a book, X-ray it, extract the authors message, criticize. You are taught the different reading techniques for reading practical books, imaginative literature, plays, poetry, history, science and mathematics, philosophy and social science.Finally, the authors offer a recommended reading list and supply reading tests whereby you can measure your own progress in reading skills, comprehension and speed. Review Quote "These four hundred pages are packed full of high matters which no one solicitous of the future of American culture can afford to overlook." Excerpt from Book Chapter 1 THE ACTIVITY AND ART OF READING This is a book for readers and for those who wish to become readers. Particularly, it is for readers of books. Even more particularly, it is for those whose main purpose in reading books is to gain increased understanding. By "readers" we mean people who are still accustomed, as almost every literate and intelligent person used to be, to gain a large share of their information about and their understanding of the world from the written word. Not all of it, of course; even in the days before radio and television, a certain amount of information and understanding was acquired through spoken words and through observation. But for intelligent and curious people that was never enough. They knew that they had to read too, and they did read. There is some feeling nowadays that reading is not as necessary as it once was. Radio and especially television have taken over many of the functions once served by print, just as photography has taken over functions once served by painting and other graphic arts. Admittedly, television serves some of these functions extremely well; the visual communication of news events, for example, has enormous impact. The ability of radio to give us information while we are engaged in doing other things -- for instance, driving a caris remarkable, and a great saving of time. But it may be seriously questioned whether the advent of modern communications media has much enhanced our understanding of the world in which we live. Perhaps we know more about the world than we used to, and insofar as knowledge is prerequisite to understanding, that is all to the good. But knowledge is not as much a prerequisite to understanding as is commonly supposed. We do not have to know everything about something in order to understand it; too many facts are often as much of an obstacle to understanding as too few. There is a sense in which we moderns are inundated with facts to the detriment of understanding. One of the reasons for this situation is that the very media we have mentioned are so designed as to make thinking seem unnecessary (though this is only an appearance). The packaging of intellectual positions and views is one of the most active enterprises of some of the best minds of our day. The viewer of television, the listener to radio, the reader of magazines, is presented with a whole complex of elements -- all the way from ingenious rhetoric to carefully selected data and statistics -- to make it easy for him to "make up his own mind" with the minimum of difficulty and effort. But the packaging is often done so effectively that the viewer, listener, or reader does not make up his own mind at all. Instead, he inserts a packaged opinion into his mind, somewhat like inserting a cassette into a cassette player. He then pushes a button and "plays back" the opinion whenever it seems appropriate to do so. He has performed acceptably without having had to think. Active Reading As we said at the beginning, we will be principally concerned in these pages with the development of skill in reading books; but the rules of reading that, if followed and practiced, develop such skill can be applied also to printed material in general, to any type of reading matter -- to newspapers, magazines, pamphlets, articles, tracts, even advertisements. Since reading of any sort is an activity, all reading must to some degree be active. Completely passive reading is impossible; we cannot read with our eyes immobilized and our minds asleep. Hence when we contrast active with passive reading, our purpose is, first, to call attention to the fact that reading can be more or less active, and second, to point out that the more active the reading the better. One reader is better than another in proportion as he is capable of a greater range of activity in reading and exerts more effort. He is better if he demands more of himself and of the text before him. Though, strictly speaking, there can be no absolutely passive reading, many people think that, as compared with writing and speaking, which are obviously active undertakings, reading and listening are entirely passive. The writer or speaker must put out some effort, but no work need be done by the reader or listener. Reading and listening are thought of as receiving communication from someone who is actively engaged in giving or sending it. The mistake here is to suppose that receiving communication is like receiving a blow or a legacy or a judgment from the court. On the contrary, the reader or listener is much more like the catcher in a game of baseball. Catching the ball is just as much an activity as pitching or hitting it. The pitcher or batter is the sender in the sense that his activity initiates the motion of the ball. The catcher or fielder is the receiver in the sense that his activity terminates it. Both are active, though the activities are different. If anything is passive, it is the ball. It is the inert thing that is put in motion or stopped, whereas the players are active, moving to pitch, hit, or catch. The analogy with writing and reading is almost perfect. The thing that is written and read, like the ball, is the passive object common to the two activities that begin and terminate the process. We can take this analogy a step further. The art of catching is the skill of catching every kind of pitch -- fast bails and curves, changeups and knucklers. Similarly, the art of reading is the skill of catching every sort of communication as well as possible. It is noteworthy that the pitcher and catcher are successful only to the extent that they cooperate. The relation of writer and reader is similar. The writer isnt trying not to be caught, although it sometimes seems so. Successful communication occurs in any case where what the writer wanted to have received finds its way into the readers possession. The writers skill and the readers skill converge upon a common end. Admittedly, writers vary, just as pitchers do. Some writers have excellent "control"; they know exactly what they want to convey, and they convey it precisely and accurately. Other things being equal, they are easier to "catch" than a "wild" writer without "control." There is one respect in which the analogy breaks down. The ball is a simple unit. It is either completely caught or not. A piece of writing, however, is a complex object. It can be received more or less completely, all the way from very little of what the writer intended to the whole of it. The amount the reader "catches" will usually depend on the amount of activity he puts into the process, as well as upon the skill with which he executes the different mental acts involved. What does active reading entail? We will return to this question many times in this book. For the moment, it suffices to say that, given the same thing to read, one person reads it better than another, first, by reading it more actively, and second, by performing each of the acts involved more skillfully. These two things are related. Reading is a complex activity, just as writing is. It consists of a large number of separate acts, all of which must be performed in a good reading. The person who can perform more of them is better able to read. > The Goals of Reading: Reading for Information and Reading for Understanding You have a mind. Now let us suppose that you also have a book that you want to read. The book consists of language written by someone for the sake of communicating something to you. Your success in reading it is determined by the extent to which you receive everything the writer intended to communicate. That, of course, is too simple. The reason is that there are two possible relations between your mind and the book, not just one. These two relations are exemplified by two different experiences that you can have in reading your book. There is the book; and here is your mind. As you go through the pages, either you understand perfectly everything the author has to say or you do not. If you do, you may have gained information, but you could not have increased your understanding. If the book is completely intelligible to you from start to finish, then the author and you are as two minds in the same mold. The symbols on the page merely express the common understanding you had before you met. Let us take our second alternative. You do not understand the book perfectly. Let us even assume -- what unhappily is not always true -- that you understand enough to know that you do not understand it all. You know the book has more to say than you understand and hence that it contains something that can increase your understanding. What do you do then? You can take the book to someone else who, you think, can read better than you, and have him explain the parts that trouble you. ("He" may be a living person or another book -- a commentary or textbook. ) Or you may decide that what is over your head is not worth bothering about, that you understand enough. In either case, you are not doing the job of reading that the book requires. That is done in only one way. Without external help of any sort, you go to work on the book. With nothing but the power of your own mind, you operate on the symbols before you in such a way that you gradually lift yourself from a state of understanding less to one of understanding more. Such elevation, accomplished by the mind working on a book, is highly skilled reading, the kind of reading that a book which challenges your understanding deserves. Thus we can roug Details ISBN0671212095 Short Title HT READ A BK REV. Pages 426 Edition Description Revised and Upd Language English ISBN-10 0671212095 ISBN-13 9780671212094 Media Book Format Paperback Series A Touchstone book Imprint Touchstone Subtitle The Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading Country of Publication United States Illustrations illustrations Place of Publication New York Edition Revised edition DOI 10.1604/9780671212094 UK Release Date 2008-06-16 NZ Release Date 2008-06-16 Author Charles Van Doren Publisher Simon & Schuster Alternative 9781476790152 DEWEY 418.4 Audience General AU Release Date 1985-12-31 Year 2008 Publication Date 2008-06-16 US Release Date 2008-06-16 We've got this At The Nile, if you're looking for it, we've got it. With fast shipping, low prices, friendly service and well over a million items - you're bound to find what you want, at a price you'll love! TheNile_Item_ID:160751059;

Price: 23.01 AUD

Location: Melbourne

End Time: 2025-02-08T03:39:42.000Z

Shipping Cost: 2.91 AUD

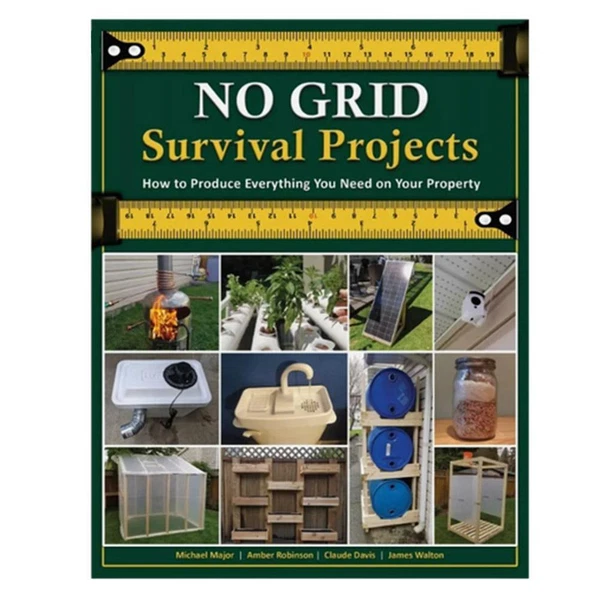

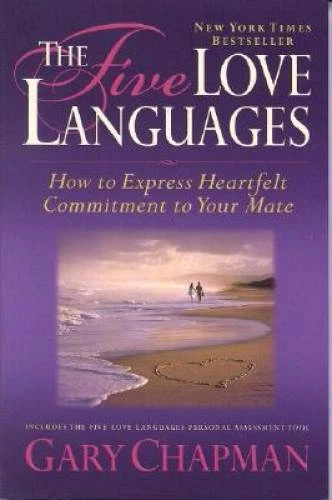

Product Images

Item Specifics

Restocking fee: No

Return shipping will be paid by: Buyer

Returns Accepted: Returns Accepted

Item must be returned within: 30 Days

ISBN-13: 9780671212094

Type: NA

Publication Name: NA

Book Title: How to Read a Book

Item Height: 210mm

Item Width: 135mm

Author: Mortimer J. Adler, Charles Van Doren

Format: Paperback

Language: English

Topic: Literature, Popular Philosophy

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Publication Year: 2008

Item Weight: 338g

Number of Pages: 426 Pages